Originally posted by xyyman:

quote:Confusing to whom?

Originally posted by the lioness,:

the term "Saharan-Arabian" has led to a lot of confusion

![[Big Grin]](biggrin.gif)

quote:the addition is based on a sample of 7, a 20 year period, data not peer reviewed

Originally posted by Amun-Ra The Ultimate:

Forget about this. This forum is about Ancient Egypt.

quote:

Originally posted by xyyman:

quote:Confusing to whom?

Originally posted by the lioness,:

the term "Saharan-Arabian" has led to a lot of confusion

quote:--Dr. Dahmane At Ali.

Back to the beginning! In April 20th, 1980 indeed, the collective “soul” of the Kabyle people, of nearly three thousand years aged, in a fabulous and unprecedented popular communion gushed from beneath the tombs of silence, the dismissed calends and the contemptible rule of the established political order in which the human stupidity had, for a moment, thought to lock their still alive burial forever.

quote:--Sarah Thiskoff, Gonder et al.

Although 2 mtDNA lineages with an African origin (haplogroups M and N) were the progenitors of all non-African haplogroups, macrohaplogroup L (including haplogroups L0–L6) is limited to sub-Saharan Africa.

quote:--Adimoolam Chandrasekar et al. 2009

The presence of M haplogroup in Ethiopia, named M1, led to the proposal that haplogroup M originated in eastern Africa, approximately 60,000 years ago, and was carried towards Asia [34].

quote:-- Semino et al.

The coding regions transitions are likely to change relatively slower than those of hypervariable segments, and hence, likely to remain intact within a clade. To assist in determining which clade to place a monophyletic unit, key coding region transitions have to be identified. In the case of M1, we were told:

We found 489C (Table 3) in all Indian and eastern-African haplogroup M mtDNAs analysed, but not in the non-M haplogroup controls, including 20 Africans representing all African main lineages (6 L1, 4 L2, 10 L3) and 11 Asians.

These findings, and the lack of positive evidence (given the RFLP status) that the 10400 C->T transition defining M has happened more than once, suggest that it has a single common origin, but do not resolve its geographic origin. Analysis of position 10873 (the MnlI RFLP) revealed that all the M molecules (eastern African, Asian and those sporadically found in our population surveys) were 10873C (Table 3). As for the non-M mtDNAs, the ancient L1 and the L2 African-specific lineages5, as well as most L3 African mtDNAs, also carry 10873C.

Conversely, all non-M mtDNAs of non-African origin analysed so far carry 10873T. These data indicate that the **transition 10400 C-->T, which defines haplogroup M**, arose on an African background characterized by the ancestral state 10873C, which is also present in four primate (common and pygmy chimps, gorilla and orangutan) mtDNA sequences.

quote:--Hans-Jürgen Bandelt et. 2006. EDS. Human Mitochondrial DNA and

"These indicate that the root of L3 gives rise to a multifurcation from a

single haplotype producing a number of distinct subclades... The

simplest explanation for this geographical distribution [haplogroups M

and N], however, is an expansion of the root type within East Africa,

where several independent L3 branches thrive, including a sister group

to L3, christened L4 (Kivisild et al. 2004; Chap. 7), followed by

divergence into haplogroups M and N somewhere between the Horn of

Africa and the Indian subcontinent. Since neither the L3 root type nor

any other descendants survive outside Africa, the root type itself must

have become extinct during a period of genetic drift in the founder

population as it diversified into haplogroups M and N, if the

diversification was outside Africa. If on the other hand the

diversification was indeed within East Africa, then Haplogroups M and

N must have either been carried out of Africa in their entirety or

subsequently have become extinct within Africa, with the singular

exception of the derived M1."

quote:--Paola Spinozzi, Alessandro Zironi .

Although Haplogroup M differentiated

soon after the out of Africa exit and it is

widely distributed in Asia (east Asia and

India) and Oceania, there is an

interesting exception for one of its more

than 40 sub-clades: M1.. Indeed this

lineage is mainly limited to the African

continent with peaks in the Horn of

Africa."

quote:-- Petraglia, M and Rose, J

“..the M1 presence in the Arabian

peninsula signals a predominant East

African influence since the Neolithic

onwards.“

quote:--SUVENDU MAJI, S. KRITHIKA and T. S. VASULU (2009)

Macrohaplogroup M (489-10400-14783-15043), excluding M1 which is east African, is distributed among most south, east and north Asians, Amerindians (containing a minority of north and central Amerindians and a majority of south Amerindians), and many central Asians and Melanesians.

quote:--Erwan Pennarun,

"No southwest Asian specific clades for M1 or U6 were discovered. U6 and M1 frequencies in North Africa, the Middle East and Europe do not follow similar patterns, and their sub-clade divisions do not appear to be compatible with their shared history reaching back to the Early Upper Palaeolithic."

[...]

U6a1 and M1b, with their coalescent ages of ~20,000–22,000 years ago and earliest inferred expansion in northwest Africa, could coincide with the flourishing of the Iberomaurusian industry, whilst U6b and M1b1 appeared at the time of the Capsian culture.

quote:--Frigi et al.

The results show that the most ancient haplogroup is L3*, which would have been introduced to North Africa from eastern sub-Saharan populations around 20,000 years ago. Our results also point to a less ancient western sub-Saharan gene flow to Tunisia, including haplogroups L2a and L3b. This conclusion points to an ancient African gene flow to Tunisia before 20,000 BP.

[...]

This conclusion points to an ancient African gene flow to Tunisia before 20,000 BP. These findings parallel the more recent findings of both archaeology and linguistics on the prehistory of Africa.

The present work suggests that sub-Saharan contributions to North Africa have experienced several complex population processes after the occupation of the region by anatomically modern humans.

Our results reveal that Berber speakers have a foundational biogeographic root in Africa and that deep African lineages have continued to evolve in supra-Saharan Africa.

quote:--Late Pleistocene Human Occupation of Northwest Africa: A Crosscheck of Chronology and Climate Change in Morocco

Regular Middle Paleolithic inventories as well as Middle Paleolithic inventories of Aterian type have a long chronology in Morocco going back to MIS 6 and are interstratified in some sites. Their potential for detecting chrono-cultural patterns is low. The transition from the Middle to Upper Paleolithic, here termed Early Upper Paleolithic—at between 30 to 20 ka—remains a most enigmatic era. Scarce data from this period requires careful and fundamental reconsidering of human presence. By integrating environmental data in the reconstruction of population dynamics, clear correlations become obvious. High resolution data are lacking before 20 ka, and at some sites this period is characterized by the occurrence of sterile layers between Middle Paleolithic deposits, possibly indicative of a very low presence of humans in Morocco. After Heinrich Event 1, there is an enormous increase of data due to the prominent Late Iberomaurusian deposits that contrast strongly with the foregoing accumulations in terms of sedimentological features, fauna, and artifact composition. The Younger Dryas again shows a remarkable decline of data marking the end of the Paleolithic. Environmental improvements in the Holocene are associated with an extensive Epipaleolithic occupation. Therefore, the late glacial cultural sequence of Morocco is a good test case for analyzing the interrelationship of culture and climate change.

quote:--J.-J. Hublin, Dental Evidence from the Aterian Human Populations of Morocco

The makers of these assemblages can therefore be seen as (1) a group of Homo sapiens predating and/or contemporary to the out-of-Africa exodus of the species, and (2) geographi- cally one of the (if not the) closest from the main gate to Eurasia at the northeastern corner of the African continent. Although Moroccan specimens have been discovered far away from this area, they may provide us with one of the best proxies of the African groups that expanded into Eurasia. Comparing them with the European and Near- Eastern human groups that immediately pre- and post-dated this exodus is therefore of crucial importance in order to elucidate the nature of the populations involved in it

[...]

quote:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929711001649

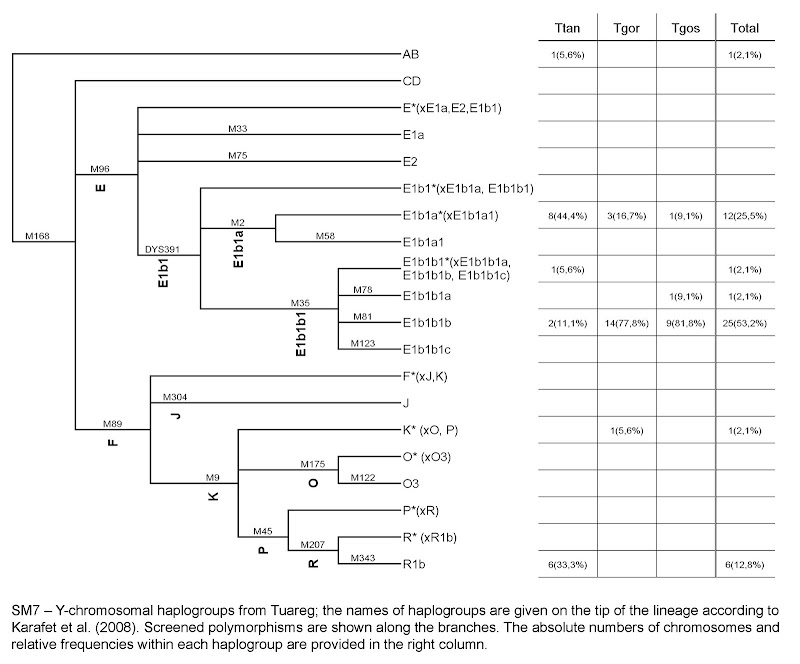

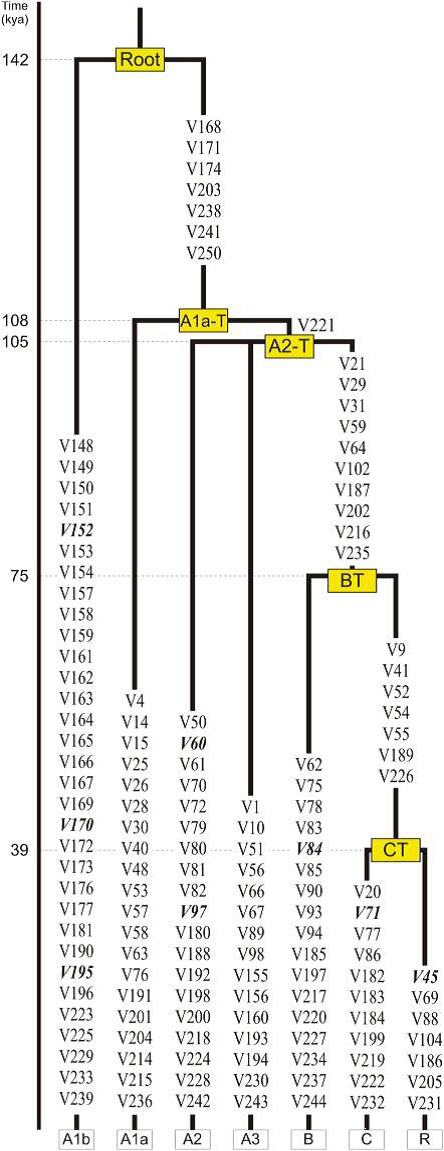

The deepest branching separates A1b from a monophyletic clade whose members (A1a, A2, A3, B, C, and R) all share seven mutually reinforcing derived mutations (five transitions and two transversions, all at non-CpG sites). To retain the information from the reference MSY tree13 as much as possible, we named this clade A1a-T (Figure 1).Within A1a-T, the transversion V221 separates A1a from a monophyletic clade (called A2-T) consisting of three branches: A2, A3, and BT, the latter being supported by ten mutations (Figure 1).

[...]

How does the present MSY tree compare with the backbone of the recently published “reference” MSY phylogeny?13 The phylogenetic relationships we observed among chromosomes belonging to haplogroups B, C, and R are reminiscent of those reported in the tree by Karafet et al.13 These chromosomes belong to a clade (haplogroup BT) in which chromosomes C and R share a common ancestor (Figure 2).

quote:http://www.isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_HapgrpA.html

Y-DNA haplogroup A contains lineages deriving from the earliest branching in the human Y chromosome tree. The oldest branching event, separating A0-P305 and A1-V161, is thought to have occurred about 140,000 years ago. Haplogroups A0-P305, A1a-M31 and A1b1a-M14 are restricted to Africa and A1b1b-M32 is nearly restricted to Africa. The haplogroup that would be named A1b2 is composed of haplogroups B through T. The internal branching of haplogroup A1-V161 into A1a-M31, A1b1, and BT (A1b2) may have occurred about 110,000 years ago. A0-P305 is found at low frequency in Central and West Africa. A1a-M31 is observed in northwestern Africans; A1b1a-M14 is seen among click language-speaking Khoisan populations. A1b1b-M32 has a wide distribution including Khoisan speaking and East African populations, and scattered members on the Arabian Peninsula.

quote:http://www.isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_YDNATreeTrunk.html

The BT haplogroup split from the root of the Y haplogroup tree 55,000 years before present (bp), probably in North East Africa. The CF(xDE) haplogroup was the common ancestor of all people who migrated outside of Africa until recent times. The defining mutation occurred 31-55,000 years bp in North East Africa and is still most common in Africa today in Ethiopia and Sudan. The DE haplogroup appeared approximately 50,000 years bp in North East Africa and subsequently split into haplogroup E that spread to Europe and Africa and haplogroup D that rapidly spread along the coastline of India and Asia to North Asia.

quote:--Dr Anna Leone, PhD

I have been working for a long time and published several articles on Roman pottery in Rome, Italy and North Africa. I have a good knowledge of all the classes of pottery that circulated in the Mediterranean from the Republican period to the 7th/8th century AD and beyond.

The period in question from AD 300 to AD 700, spans more that political transitions: it sees the adoption of Christianity (during the Las Imperial period and the Byzantine times), the Vandal rule and the adoption of Arianism and the Arab/Muslim imposition.

quote:Ancient History Sourcebook: Procopius of Caesarea: Gaiseric & The Vandal Conquest of North Africa, 406 - 477 CE

"And yet the number of the Vandals and Alans was said in former times, at least, to amount to no more than fifty thousand men. However, after that time by their natural increase among themselves and by associating other barbarians with them they came to be an exceedingly numerous people."

quote:Racist beast, STFU!

Originally posted by the lioness,:

they can't deal with it so they spam other stuff, shyt is funny

quote:http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/afalou%20man

: one of an Upper Paleolithic people of northern Africa closely related to Cro-Magnon man but having a broader nose, a sloping forehead, and heavy brow ridges

quote:

Craniometric data from seven human groups (Tables 3, 4) were subjected to principal components analysis, which allies the early Holocene population at Gobero (Gob-e) with mid-Holocene “Mechtoids” from Mali and Mauritania [18],[26],[27] and with Late Pleistocene Iberomaurusians and early Holocene Capsians from across the Maghreb:

quote:--Lawrence Barham

*Frequently termed Mechta-Afalou or Mechtoid, these were a skeletally robust people and definitely African in origin, though attempts, such as those of Ferembach (1985), to establish similarities with much older and rarer Aterian skeletal remains are tenuous given the immense temporal separation between the two (Close and Wendorf 1990). At the opposite end of the chronological spectrum, dental morphology does suggest connections with later Africans, including those responsible for the Capsian Industry (Irish 2000) and early mid-Holocene human remains from the western half of the Sahara (Dutour 1989), something that points to the Maghreb as one of the regions from which people recolonised the desert (MacDonald 1998).

quote:--Nick Brooks et al. (2004)

Evidence from throughout the Sahara indicates that the region experienced a cool, dry and windy climate during the last glacial period, followed by a wetter climate with the onset of the current interglacial, with humid conditions being fully established by around 10,000 years BP, when we see the first evidence of a reoccupation of parts of the central Sahara by hunter gathers, most likely originating from sub-Saharan Africa (Cremaschi and Di Lernia, 1998; Goudie, 1992; Phillipson, 1993; Ritchie, 1994; Roberts, 1998).

[...]

Conical tumuli, platform burials and a V-type monument represent structures similar to those found in other Saharan regions and associated with human burials, appearing in sixth millennium BP onwards in northeast Niger and southwest Libya (Sivilli, 2002). In the latter area a shift in emphasis from faunal to human burials, complete by the early fifth millennium BP, has been interpreted by Di Lernia and Manzi (2002) as being associated with a changes in social organisation that occurred at a time of increasing aridity. While further research is required in order to place the funerary monuments of Western Sahara in their chronological context, we can postulate a similar process as a hypothesis to be tested, based on the high density of burial sites recorded in the 2002 survey. Fig. 2: Megaliths associated with tumulus burial (to right of frame), north of Tifariti (Fig. 1). A monument consisting of sixty five stelae was also of great interest; precise alignments north and east, a division of the area covered into separate units, and a deliberate scattering of quartzite inside the structure, are suggestive of an astronomical function associated with funerary rituals. Stelae are also associated with a number of burial sites, again suggesting dual funerary and astronomical functions (Figure 2). Further similarities with other Saharan regions are evident in the rock art recorded in the study area, although local stylistic developments are also apparent. Carvings of wild fauna at the site of Sluguilla resemble the Tazina style found in Algeria, Libya and Morocco (Pichler and Rodrigue, 2003), although examples of elephant and rhinoceros in a naturalistic style reminiscent of engravings from the central Sahara believed to date from the early Holocene are also present.

quote:There is nothing of actual fact in it, Asmahan Bekada. So all you can do now, is repeat your same rant. As is displayed by multiple sources I have posts.

Originally posted by the lioness,:

they can't deal with it so they spam other stuff, shyt is funny

quote:Shyt is indeed funny, when it can be traced back to a lie. And this all you support! And it's all here for the people to read about it. Something you fear deeply. Funny indeed.

Originally posted by the lioness,:

they can't deal with it so they spam other stuff, shyt is funny

quote:Sourced by: Time Magazine.

For years, Italian Anthropologist Fabrizio Mori has been trekking into the Libyan Desert to look for graffiti, ancient inscriptions on rocks. Near the oasis of Ghat, 500 miles south of the Mediterranean coast, he found on his last expedition a shallow cave with many graffiti scratched on its walls. When he dug into the sandy floor, he found a peculiar bundle: a goatskin wrapped around the desiccated body of a child. The entrails had been removed and replaced by a bundle of herbs.

Such deliberate mummification was practiced chiefly by the ancient Egyptians. But when Dr. Mori took the mummy back to Italy and had its age measured by the carbon 14 method, it proved to be 5,400 years old—considerably older than the oldest known civilization in the valley of the Nile 900 miles to the east.

The discovery suggested a clue to one of the great puzzles of Egyptology: Where was the birthplace of Egyptian culture? Although many authorities believe it is the world's oldest, they have been perplexed by the fact that it did not develop gradually in the Nile Valley. About 3200 B.C. the First Dynasty appeared there suddenly and full grown, with an elaborate religion, laws, arts and crafts, and a system of writing. Until that time the Nile Valley was apparently inhabited by neolithic people on a low cultural level. Dr. Mori's mummy provides support for the theory that Egyptian culture grew by slow stages in the Sahara, which was not then a desert. When the climate grew insupportably dry, the already civilized Egyptians took refuge in the Nile Valley, and the sands of the Sahara swept over their former home.

The mummy does not prove that there is a civilization buried in the Sahara but it does mean that, in the next few years, the desert will be swarming with anthropologists looking for one.

quote:--Nick Brooks et al.

Evidence from throughout the Sahara indicates that the region experienced a cool, dry and windy climate during the last glacial period, followed by a wetter climate with the onset of the current interglacial, with humid conditions being fully established by around 10,000 years BP, when we see the first evidence of a reoccupation of parts of the central Sahara by hunter gathers, most likely originating from sub-Saharan Africa (Cremaschi and Di Lernia, 1998; Goudie, 1992; Phillipson, 1993; Ritchie, 1994; Roberts, 1998).

[...]

Conical tumuli, platform burials and a V-type monument represent structures similar to those found in other Saharan regions and associated with human burials, appearing in sixth millennium BP onwards in northeast Niger and southwest Libya (Sivilli, 2002). In the latter area a shift in emphasis from faunal to human burials, complete by the early fifth millennium BP, has been interpreted by Di Lernia and Manzi (2002) as being associated with a changes in social organisation that occurred at a time of increasing aridity. While further research is required in order to place the funerary monuments of Western Sahara in their chronological context, we can postulate a similar process as a hypothesis to be tested, based on the high density of burial sites recorded in the 2002 survey. Fig. 2: Megaliths associated with tumulus burial (to right of frame), north of Tifariti (Fig. 1). A monument consisting of sixty five stelae was also of great interest; precise alignments north and east, a division of the area covered into separate units, and a deliberate scattering of quartzite inside the structure, are suggestive of an astronomical function associated with funerary rituals. Stelae are also associated with a number of burial sites, again suggesting dual funerary and astronomical functions (Figure 2). Further similarities with other Saharan regions are evident in the rock art recorded in the study area, although local stylistic developments are also apparent. Carvings of wild fauna at the site of Sluguilla resemble the Tazina style found in Algeria, Libya and Morocco (Pichler and Rodrigue, 2003), although examples of elephant and rhinoceros in a naturalistic style reminiscent of engravings from the central Sahara believed to date from the early Holocene are also present.

quote:Sahara: Barrier or corridor? Nonmetric cranial traits and biological affinities of North African late Holocene populations.

The Garamantes flourished in southwestern Libya, in the core of the Sahara Desert ~3,000 years ago and largely controlled trans-Saharan trade. Their biological affinities to other North African populations, including the Egyptian, Algerian, Tunisian and Sudanese, roughly contemporary to them, are examined by means of cranial nonmetric traits using the Mean Measure of Divergence and Mahalanobis D(2) distance. The aim is to shed light on the extent to which the Sahara Desert inhibited extensive population movements and gene flow. Our results show that the Garamantes possess distant affinities to their neighbors. This relationship may be due to the Central Sahara forming a barrier among groups, despite the archaeological evidence for extended networks of contact. The role of the Sahara as a barrier is further corroborated by the significant correlation between the Mahalanobis D(2) distance and geographic distance between the Garamantes and the other populations under study. In contrast, no clear pattern was observed when all North African populations were examined, indicating that there was no uniform gene flow in the region.

quote:http://anthropology.net/2008/08/14/the-kiffian-tenerean-occupation-of-gobero-niger-perhaps-the-largest-collection-of-early-mid-holocene-people-in-africa/

This site has been called Gobero, after the local Tuareg name for the area. About 10,000 years ago (7700–6200 B.C.E.), Gobero was a much less arid environment than it is now. In fact, it was actually a rather humid lake side hometown of sorts for a group of hunter-fisher-gatherers who not only lived their but also buried their dead there. How do we know they were fishing? Well, remains of large nile perch and harpoons were found dating to this time period.

quote:

The older occupants have craniofacial dimensions that demonstrate similarities with mid-Holocene occupants of the southern Sahara and Late Pleistocene to early Holocene inhabitants of the Maghreb.

quote:

These early occupants abandon the area under arid conditions and, when humid conditions return ~4600 B.C.E., are replaced by a more gracile people with elaborated grave goods including animal bone and ivory ornaments.

quote:

Principal components analysis of craniometric variables closely allies the early Holocene occupants at Gobero with a skeletally robust, trans-Saharan assemblage of Late Pleistocene to mid-Holocene human populations from the Maghreb and southern Sahara.

quote:--(doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002995.g006)

Figure 6. Principal components analysis of craniofacial dimensions among Late Pleistocene to mid-Holocene populations from the Maghreb and southern Sahara.

Plot of first two principal components extracted from a mean matrix for 17 craniometric variables (Tables 4, 7) in 9 human populations (Table 3) from the Late Pleistocene through the mid-Holocene from the Maghreb and southern Sahara. Seven trans-Saharan populations cluster together, whereas Late Pleistocene Aterians (Ater) and the mid-Holocene population at Gobero (Gob-m) are striking outliers. Axes are scaled by the square root of the corresponding eigenvalue for the principal component. Abbreviations: Ater, Aterian; EMC, eastern Maghreb Capsian; EMI, eastern Maghreb Iberomaurusian; Gob-e, Gobero early Holocene; Gob-m, Gobero mid-Holocene; Mali, Hassi-el-Abiod, Mali; Maur, Mauritania; WMC, western Maghreb Capsian; WMI, western Maghreb Iberomaurusian.

quote:

Craniometric data from seven human groups (Tables 3, 4) were subjected to principal components analysis, which allies the early Holocene population at Gobero (Gob-e) with mid-Holocene “Mechtoids” from Mali and Mauritania [18], [26], [27] and with Late Pleistocene Iberomaurusians and early Holocene Capsians from across the Maghreb (see cluster in Figure 6). The striking similarity between these seven human populations confirms previous suggestions regarding their affinity [18] and is particularly significant given their temporal range (Late Pleistocene to mid-Holocene) and trans-Saharan geographic distribution (across the Maghreb to the southern Sahara).

quote:--Paul C. Sereno

Trans-Saharan craniometry. Principal components analysis of craniometric variables closely allies the early Holocene occupants at Gobero, who were buried with Kiffian material culture, with Late Pleistocene to mid-Holocene humans from the Maghreb and southern Sahara referred to as Iberomaurusians, Capsians and “Mechtoids.” Outliers to this cluster of populations include an older Aterian sample and the mid-Holocene occupants at Gobero associated with Tenerean material culture.

quote:Gasse, F., 2002. Diatom-inferred salinity and carbonate oxygen isotopes in Holocene waterbodies of the western Sahara and Sahel (Africa). Quaternary Science Reviews: 717-767.

The reconstruction of human cultural patterns in relation to environmental variations is an essential topic in modern archaeology.

In western Africa, a first Holocene humid phase beginning c. 11,000 years BP is known from the analysis of lacustrine sediments (Riser, 1983 ; Gasse, 2002). The monsoon activity increased and reloaded hydrological networks (like the Saharan depressions) leading to the formation of large palaeolakes. The colonisation of the Sahara by vegetation, animals and humans was then possible essentially around the topographic features like Ahaggar (fig. 1). But since 8,000 years BP, the climate began to oscillate towards a new arid episode, and disturbed the ecosystems (Jolly et al., 1998; Jousse, 2003).

First, the early Neolithics exploited the wild faunas, by hunting and fishing, and occupied small sites without any trace of settlement in relatively high latitudes. Then, due to the climatic deterioration, they had to move southwards.

This context leads us to consider the notion of refugia. Figure 1 presents the main zones colonised by humans in western Africa. When the fossil valleys of Azaouad, Tilemsi and Azaouagh became dry, after ca. 5,000 yr BP, humans had to find refuges in the Sahelian belt, and gathered around topographic features (like the Adrar des Iforas, and the Mauritanians Dhar) and major rivers, especially the Niger Interior Delta, called the Mema.

Whereas the Middle Neolithic is relatively well-known, the situation obviously becomes more complex and less information is available concerning local developments in late Neolithic times.. Only some cultural affiliations existed between the populations of Araouane and Kobadi in the Mema. Elsewhere, and especially along the Atlantic coast and in the Dhar Tichitt and Nema, the question of the origin of Neolithic peopling remains unsolved.

A study of the palaeoenvironment of those refugia was performed by analysing antelopes ecological requirements (Jousse, submitted). It shows that even if the general climate was drying from 5,000 – 4,000 yr BP in the Sahara and Sahel, edaphic particularities of these refugia allowed the persistence of local gallery forest or tree savannas, where humans and animals could have lived (fig. 2). At the same time, cultural innovation like agriculture, cattle breeding, social organisation in villages are recognised. For the moment, the relation between the northern and the southern populations are not well known.

How did humans react against aridity? Their dietary behaviour are followed along the Holocene, in relation with the environment, demographic expansion, settling process and emergence of productive activities.

- The first point concerns the pastoralism. The progression of cattle pastoralism from eastern Africa (fig. 3) is recorded from 7,400 yr BP in the Ahaggar and only from 4,400 yr BP in western Africa. This trend of breeding activities and human migrations can be related to climatic evolution. Since forests are infested by Tse-Tse flies preventing cattle breeding, the reduction of forest in the low-Sahelian belt freed new areas to be colonised. Because of the weakness of the archaeozoological material available, it is difficult to know what was the first pattern of cattle exploitation.

- A second analysis was carried on the resources balance, between fishing-hunting-breeding activities. The diagrams on figures 4 and 5 present the number of species of wild mammals, fishes and domestic stock, from a literature compilation. Fishing is known around Saharan lakes and in the Niger. Of course, it persisted with the presence of water points and even in historical times, fishing became a specialised activity among population living in the Niger Interior Delta. Despite the general environmental deterioration, hunting does not decrease thanks to the upholding of the vegetation in these refugia (fig. 2). On the contrary, it is locally more diversified, because at this local scale, the game diversity is closely related to the vegetation cover. Hence, the arrival of pastoral activities was not prevalent over other activities in late Neolithic, when diversifying resources appeared as an answer to the crisis.

This situation got worse in the beginning of historic times, from 2,000 yr BP, when intense settling process and an abrupt aridity event (Lézine & Casanova, 1989) led to a more important perturbation of wild animals communities. They progressively disappeared from the human diet, and the cattle, camel and caprin breeding prevailed as today.

quote:--Nick Brooks (2013): Beyond collapse: climate change and causality during the Middle Holocene Climatic Transition, 6400–5000 years before present, Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 112:2, 93-104

The Middle Holocene, and more precisely the period from around 6400 BP and 5000 BP, was a period of profound environmental change, during which the global climate underwent a systematic reorganisation as the warm, humid post-glacial climate of the Early Holocene gave way to a climatic configuration broadly similar to that of today (Brooks, 2010; Mayewski et al., 2004). The most prominent manifestations of this transition were a cooling at middle and high latitudes and high altitudes (Thompson et al., 2006), a transition from relatively humid to arid conditions in the NHST (Brooks, 2006, 2010; deMenocal et al., 2000) and the establishment of a regular El Niño after a multimillennial period during which is was rare or absent (Sandweiss et al., 2007).

This “Middle Holocene Climatic Transition” (MHCT) represented a stepwise acceleration of climatic trends that had commenced in the 9th millennium BP in some regions (Jung et al., 2004), and entailed a long-term shift towards cooler and more arid conditions, punctuated by episodes of abrupt climatic change. Around 6400–6300 BP, palaeo-environmental evidence indicates abrupt lake recessions and increased aridity in northern Africa, western Asia, South Asia and northern China, and the advance of glaciers in Europe and elsewhere (Damnati, 2000; Enzel et al., 1999; Jung et al., 2004; Linstädter & Kröpelin, 2004; Mayewski et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2000).

Ocean records suggest a cold-arid episode around 5900 BP (Bond et al., 1997), followed in the Sahara by an abrupt shift to aridity around 5800–5700 BP, evident in terrestrial records from the Libyan central Sahara and marine records from the Eastern Tropical Atlantic (Cremaschi, 2002; di Lernia, 2002; deMenocal et al., 2000). From about 5800–5700 BP to 5200–5000 BP, aridification intensified in the Sahara (deMenocal et al., 2000), South Asia (Enzel et al., 1999), north-central China (Zhang et al., 2000; Xiao et al., 2004) and the Arabian Peninsula (Parker et al., 2006). Over the same period, drought conditions prevailed in the Eastern Medi- terranean (Bar-Matthews & Ayalon, 2011), the Zagros Mountains of Iran (Stevens et al., 2006) and County Mayo in Ireland (Caseldine et al., 2005), while river flow into the Cariaco Basin of northern South America decreased (Haug et al., 2001). An abrupt cold-arid epi- sode around 5200 BP is evident in environmental records from Europe, Africa, western Asia, China and South America, (Caseldine et al., 2005; Gasse, 2002; Magny & Haas, 2004; Parker et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 1995).

The above evidence indicates that the MHCT was associated with a weakening of monsoon systems across the globe, and the southward retreat of monsoon rains in the NHST (Lézine, 2009). However, these changes coin- cided with climatic reorganisation outside of the global monsoon belt, as indicated by the onset of El Niño and evidence of large changes in climate at middle and high latitudes. The ultimate driving force behind these changes was a decline in the intensity of summer solar radiation outside the tropics, resulting from long-term changes in the angle of the Earth’s axis of rotation relative to its orbital plane. This was translated into abrupt changes in climate by non-linear feedback processes within the climate system (Brooks, 2004; deMenocal et al., 2000; Kukla & Gavin, 2004).

[...]

In the Sahara, population agglomeration is also evident in certain areas such as the Libyan Fezzan, which (albeit much later) also saw the emergence of an indigenous Saharan “civilization” in the form of the Garamantian Tribal Confederation, the development of which has been described explicitly in terms of adaptation to increased aridity (Brooks, 2006; di Lernia et al., 2002; Mattingly et al., 2003).

quote:Why is the only references to anthropology not even a real anthropological study, but just another genetic study, with more anthropological guesswork? It's weird, staking up lies with more lies.

Originally posted by xyyman:

He! He! He1 You didn't need to nuke him.

This is informative..on hg-A in NW Africa and Arabia

quote:

quote:--B Quintáns, V Álvarez-Iglesias, A Salas, C Phillips, M.V Lareu, A Carracedo

Abstract

The development of new methodologies for high-throughput SNP analysis is one of the most stimulating areas in genetic research. Here, we describe a rapid and robust assay to simultaneously genotype 17 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) coding region SNPs by minisequencing using SNaPshot. SNaPshot is a methodology based on a single base extension of an unlabeled oligonucleotide with labeled dideoxy terminators. The set of SNPs implemented in this multiplexed SNaPshot reaction allow us to allocate common mitochondrial West Eurasian haplotypes into their corresponding branch in the mtDNA skeleton, with special focus on those haplogroups lacking unambiguous diagnostic positions in the first and second hypervariable regions (HVS-I/II; by far, the most common segments analyzed by sequencing). Particularly interesting is the set of SNPs that subdivide haplogroup H; the most frequent haplogroup in Europe (40–50%) and one of the most poorly characterized phylogenetically in the HVS-I/II region. In addition, the polymorphic positions selected for this multiplex reaction increase considerably the discrimination power of current mitochondrial analysis in the forensic field and can also be used as a rapid screening tool prior to full sequencing analysis. The method has been validated in a sample of 266 individuals and shows high accuracy and robustness avoiding both the use of alternative time-consuming classical strategies (i.e. RFLP typing) and the need for high quantities of DNA template.

quote:I have present work from 2013, as prior and post data, you dumbo.

Originally posted by the lioness,:

Troll Patrol at the present time, 2013, which population has more African ancestry Maghrebians or Egyptians?

quote:He does need to nuke me.

Originally posted by xyyman:

He! He! He1 You didn't need to nuke him.

This is informative..on hg-A in NW Africa and Arabia

quote:

quote:If we want to understand the population inhabitation of today, we need to understand anthropology and archeology showing the past. Posting genetics with guesswork is not going to cut it.

Originally posted by the lioness,:

quote:He does need to nuke me.

Originally posted by xyyman:

He! He! He1 You didn't need to nuke him.

This is informative..on hg-A in NW Africa and Arabia

quote:

so he doesn't have to address modern demographics

so he spams on who they were 10,000 years ago.

Modern Demographics 2013,

this is what Troll Patrol doesn't understand. So he goes into knee jerk mode

A lot of thes articles are about who the population of the Maghreb are today in 2013.

People here can't deal with that so they go back 10,000 and start talking about who they were when the sahara was green.

It's avoidance

quote:Domestication Processes and Morphological Change

Little is known about the beginnings and spread of food production in the tropics, but recent research suggests that definitions that depend on morphological change may hamper recognition of early farming in these regions. The earliest form of food production in Africa developed in arid tropical grasslands. Animals were the earliest domesticates, and the mobility of early herders shaped the development of social and economic systems. Genetic data indicate that cattle were domesticated in North Africa and suggest domestication of two different African wild asses, in the Sahara and in the Horn. Cowpeas and pearl millet were domesticated several thousand years later, but some intensively used African plants have never undergone morphological change. Morphological, genetic, ethnoarchaeological, and behavioral research reveals relationships between management, animal behavior, selection, and domestication of the donkey. Donkeys eventually showed phenotypic and morphological changes distinctive of domestication, but the process was slow. This African research on domestication of the donkey and the development of pastoralism raises questions regarding how we conceptualize hunter-gatherer versus food-producer land use. It also suggests that we should focus more intently on the methods used to recognize management, agropastoral systems, and domestication events.

This paper was submitted 13 XI 09, accepted 02 XII 10, and electronically published 08 VI 11.

The question of whether understanding of the beginnings of food production is being constrained by definitions and methods of detection that focus on morphological change rather than management is becoming a major theme in studies of the origins of agriculture. Recent research in the humid tropics of southeastern Asia and the Pacific suggests that definitions that depend on morphological change hamper recognition of early farming in these areas (Bayliss-Smith 2007; Denham 2007, 2011). This perspective has so far centered on plants of the humid tropics that have a history of long-term cultivation in agricultural systems but lack morphological change (Denham 2007; Kahlheber and Neumann 2007; Yen 1989). Another feature of both humid and arid tropical agricultural practices that has strained conceptions of early agricultural systems is the variety of economic activities—including fishing, gathering, hunting, cultivation, and herding—that may be combined in complex and diverse subsistence systems (Kahlheber and Neumann 2007; Marshall and Hildebrand 2002; for North America, Smith 2001, 2011).

In their approach to definitions and the question of whether morphological change is an effective marker of domestication, Jones and Brown (2007) focus on selection processes and timing rather than on region. They contend that under certain circumstances, practices of cultivation and protective tending could have resulted in stable long-term systems of food production that depended on plants and animals lacking distinctively domestic morphological and genetic characteristics. Reproductive isolation and morphological change, Jones and Brown (2007) go on to suggest, are linked with later stages of agricultural development, when human populations expanded and people removed plants and animals from their wild ranges.

There is a growing appreciation, however, of differences among species in time elapsed before domestication processes are readily detectable and of variability in the sensitivity of methods that can be brought to bear on any given taxon. In a detailed study of the domestication of goats in western Asia, Zeder (Zeder 2008; Zeder and Hesse 2000) used regional and age- and sex-based variability in animal size to document early herd management, which was followed by diminution in size. In the absence of clear morphological indicators, evidence for management—culling, corralling, and milking—has also been key to a better understanding of early phases of domestication of the horse (Outram et al. 2009). The discovery by Rossel et al. (2008) that donkeys used by Egyptian pharaohs for transport at approximately 5000 cal BP (historic date 3000 BC; table 1) remained morphologically wild 1,000 years after they were thought to have been first domesticated further emphasizes possibilities for underestimating the timing of domestication of large mammals and draws attention to species-specific pathways to domestication (see also Zeder 2011).

Table 1. Key African animal and plant domesticates, with summaries of sites, date ranges, and arguments for management or domestication processes

http://www.jstor.org/literatum/publisher/jstor/journals/content/curranth/2011/658481/658389/20111013/images/large/tb1.jpeg

In the light of these different emphases on global, regional, and taxon-specific impacts of late morphological change on general understanding of early food production, we evaluate current perspectives on the beginnings of food production in Africa, a continent that represents the world’s largest tropical landmass. We reexamine evidence of early animal and plant domesticates and employ ethnoarchaeological data on donkey management and breeding behavior to examine species-specific domesticatory practices that influenced selection and the likelihood of morphological change. These analyses allow us to return to the larger question of Africa’s contribution to understanding variability in early agricultural systems worldwide. In most of Africa, pastoralism is considered the earliest form of agriculture, followed by plant cultivation and adoption of mixed herding-cultivation systems.

Early Food Production in AfricaJump To Section...

Africanists have built up a picture of the beginnings of food production in which early dependence on domestic animals and increasing reliance on mobility guided the development of social and economic systems of the Early Holocene and resulted in late domestication of African plants. Specific themes that have emerged include locally and socially contingent responses to large-scale climatic change, domestication of cattle for food and donkeys for transport, intensive hunting and possible management of Barbary sheep, long-term reliance on a broad range of wild plants and animals, and late domestication of African plants.

In this review of the African evidence, we see domestication as a microevolutionary process that transformed animal and plant communities and human societies (see Clutton-Brock 1992), but we examine rather than assume relationships between domestication and long-term genetic and morphological change (see also Vigne et al. 2011). We follow Zeder (2009, 2011; Rindos 1984) in emphasizing long-term coevolutionary relations between people, animals, and plants, but unlike Rindos (1984), we also highlight the intentional role that individuals played in selection (Hildebrand 2003b; Marshall and Hildebrand 2002). Pastoralism is also an important concept for discussions of the beginnings of food production in Africa, and this, we argue, differs from herding or simple keeping of animals because pastoralists rely on moving livestock to pasture and emphasize the social and symbolic role of domestic animals (Dyson-Hudson and Dyson-Hudson 1980; Smith 2005; Spear and Waller 1993). This does not necessarily imply, however, a diet heavily based on domestic animals. Historically, African pastoralists prioritized the needs of their herds in scheduling activities and locating settlements (McCabe 2004; Western and Dunne 1979), but they usually relied on a broad range of complementary subsistence strategies ranging from seasonal cultivation, fishing, hunting, and gathering to food exchange or trade (Dyson-Hudson and Dyson-Hudson 1980; Evans-Pritchard 1940; Schneider 1979). As a result, it is overly simplistic to rely on high proportions of domestic animal bones to differentiate pastoral from hunter-gatherer or farming sites. Multiple lines of evidence are necessary, including households oriented to mobility—with slope, soil, and vegetation characteristics organized around the needs of domestic herds (Western and Dunne 1979)—animal pens, dung deposits (Shahack-Gross, Marshall, and Weiner 2003; Shahack-Gross, Simons, and Ambrose 2008), milk residues (see Evershed et al. 2008), livestock-focused rock art, and ritual livestock burials (di Lernia 2006).

Domesticatory Settings: Climatic and Social Variability and Subsistence Intensification

Large-scale climate change forms the backdrop to the beginnings of food production in northeastern Africa (Kröpelin et al. 2008). Hunter-gatherer communities deserted most of the northern interior of the continent during the arid glacial maximum and took refuge along the North African coast, the Nile Valley, and the southern fringes of the Sahara (Barich and Garcea 2008; Garcea 2006; Kuper and Kröpelin 2006). During the subsequent Early Holocene African humid phase, from the mid-eleventh to the early ninth millennium cal BP, ceramic-using hunter-gatherers took advantage of more favorable savanna conditions to resettle much of northeastern Africa (Holl 2005; Kuper and Kröpelin 2006). Evidence of domestic animals first appeared in sites in the Western Desert of Egypt, the Khartoum region of the Nile, northern Niger, the Acacus Mountains of Libya, and Wadi Howar (Garcea 2004, 2006; Pöllath and Peters 2007; fig. 1).

During the Early and mid-Holocene, diverse hunter-gatherer groups lived close to permanent water in widely separated regions of northeastern Africa, from the Acacus to Lake Victoria (Caneva 1988; Garcea 2006; Holl 2005; Prendergast and Lane 2010). Ethnoarchaeological research suggests that this social and economic variability played a significant role in pathways to food production in Africa. Recent hunter-gatherers with long-term investment in hive and trap construction and delayed-return social systems and limited sharing have historically been able to accommodate more easily property-rights issues arising out of time investment in agriculture than have those with highly egalitarian norms (Brooks, Gelburd, and Yellen 1984; Dale, Marshall, and Pilgram 2004; Marshall 2000; Smith 1998; Woodburn 1982). Moreover, cattle herding requires significantly greater commitment than cultivation because foragers can tend crops intermittently and accommodate them into flexible hunter-gatherer schedules, whereas animal herds require protection against predators and constant attention (Dale, Marshall, and Pilgram 2004; Marshall 2000). As a result, Africanists have hypothesized that domestication of cattle is more likely to have been undertaken and pastoralism adopted in regions of northeastern Africa that were occupied by complex rather than highly mobile egalitarian hunter-gatherers (Marshall and Hildebrand 2002).

Arguments that complex or delayed-return systems of social organization existed in the Acacus, the Sudanese Nile Valley, and some other regions of the African Early to mid-Holocene are based on elaboration of material culture, including manufacture of ceramics and storage facilities in these areas and highly patterned use of rock-shelter sites and local landscapes (Barich 1987; di Lernia 1999, 2001; Garcea 2004; McDonald 2008). Significant investment in living spaces and limited movement are indicated by hut construction at Nabta Playa in the Acacus Mountains and the northern Sudanese Nile Valley and by isotopic analyses at Gobero in Niger and Acacus sites (Barich 1987; Garcea 2006; Sereno et al. 2008; Tafuri et al. 2006). In the central Sahara, the Sudanese Nile Valley, and the Acacus, human burials are common (Caneva 1988; Honegger 2004; Sereno et al. 2008). Garcea (2004) and di Lernia (1999, 2001) argue that their presence in the Late Acacus phase (ca. 10,250–9600 to 9890–9440 cal BP) may relate to group identities and rights to land.

North African hunter-gatherers of the Early and mid-Holocene employed highly diverse subsistence as well as social systems. Wild cattle (Bos primigenius) were hunted along the Mediterranean coast and the Nile Valley, and small numbers of wild ass (Equus africanus) were also present in many sites (Alhaique and Marshall 2009; Gautier 1987a; Marshall 2007). Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) were the most common animal hunted across North Africa at this time (di Lernia 2001; Gautier 1987a; Saxon et al. 1974). In the Late Acacus sites of Ti-n-Torah, Uan Tabu, and Uan Afuda, intensive exploitation of wild cereals (e.g., Echinochloa, Panicum, Setaria, Digitaria, and Pennisetum) is associated with heavy grindstone use (di Lernia 1999; Garcea 2001; Mercuri 2001; fig. 1). A similar set of wild grass seeds were harvested, processed, and stored in the eastern Sahara during the late tenth and early ninth millennia at Nabta Playa, site E-75-6 (Wasylikowa et al. 1993; Wendorf and Schild 1998; for radiocarbon dates, see table 2). Along the Sudanese Nile, a variety of wild mammals were hunted in conjunction with fishing for large deepwater fish and intensive grindstone use (Caneva 1988; Haaland 1987).

http://www.jstor.org/literatum/publisher/jstor/journals/content/curranth/2011/658481/658389/20111013/images/large/tb2.jpeg

Taming of Barbary sheep.

There has been a recurrent suggestion that some North Africans penned and culled Barbary sheep herds during early phases of the Holocene (di Lernia 1998, 2001; Garcea 2006; Saxon et al. 1974; table 1). Earlier arguments for management without morphological change were based on young male–dominated culling profiles from the sites of Tamar Hat and Haua Fteah on the Mediterranean coast (Saxon et al. 1974; Smith 2008; fig. 1). More recent evidence is based on the presence of dung accumulations in the rear of rock-shelter sites occupied by complex hunter-gatherers during the tenth and early ninth millennia cal BP in the Libyan Acacus at Uan Afuda, Uan Tabu, and Fozzigiaren (Cremaschi and Trombino 2001; di Lernia 2001; Garcea 2006). Di Lernia (2001) argues that dense dung deposits in these rock shelters differ from natural dung accumulations characterized by loose and scattered pellet matrices and result instead from use of shelters for corralling animals. Micromorphological analyses of the “dung layer” sediments suggest trampling and indicate the presence of spherulites common in caprine dung, and studies of the plant remains indicate a selected range of plant species suggestive of foddering (Castelletti et al. 1999; di Lernia 2001; Mercuri 1999). Interestingly, Livingstone Smith (2001) notes that hunter-gatherer pottery of Late Acacus levels at Uan Afuda is dung tempered, a characteristic of later pastoral ceramics. The number of Barbary sheep remains declines in later sites, however, and there are no dung deposits that suggest subsequent emphasis on Barbary sheep (di Lernia 1999; Garcea 2001, 2004). Taken together, the micromorphological and archaeological evidence for dung accumulation resulting from penning of Barbary sheep in the Late Acacus rock shelters is suggestive, but additional faunal data and dung deposits are needed from open-air sites.

Domestication of African cattle?

The evidence for taming of wild cattle during the Early Holocene provides an interesting parallel to that for management of Barbary sheep. Wendorf and colleagues (Gautier 1987b; Wendorf and Królik 2001; Wendorf and Schild 1998; Wendorf, Schild, and Close 1984) have argued that seasonally settled hunter-gatherers of the Nabta Playa region (fig. 1) domesticated African cattle in the Western Desert of Egypt during the eleventh to tenth millennium cal BP (reviews of arguments in Gifford-Gonzalez 2005; table 2). Domestic sheep and goats, on the other hand, were introduced to Africa from southwestern Asia during the early eighth millennium cal BP and postdate the appearance of cattle at all sites except Uan Muhaggiag (Gautier 2001; Linseele 2010; Linseele et al. 2010). The independent domestication of African cattle has been tied to arid episodes, the desire of hunter-gatherers for increased short-term predictability in food resources, and the difficulty of intensifying plant foods under these conditions (Marshall and Hildebrand 2002). Bos remains are ubiquitous in sites of the Nabta and Bir Kiseiba regions (fig. 1) from the eleventh to the tenth millennium cal BP (table 2) but in very small numbers, precluding detailed analyses of morphometric change or reconstruction of culling profiles (Gautier 2001). Linseele (2004) has demonstrated, however, that size decrease is not a useful indicator of domestication in northeastern Africa because the size of African Bos primigenius varied regionally and temporally and because ancient Egyptian longhorn cattle overlapped in size with some wild cattle populations.

Close and Wendorf (1992) and Gautier (1984b, 1987b) also argued, largely on the basis of a well and a watering basin at site E-75-6, that the repeated presence of water-dependent North African B. primigenius in Western Desert sites during the tenth and ninth millennia cal BP (table 2) reflected range extension facilitated by management and watering of cattle (table 1). Bos cranial remains in a human grave at El Barga in northern Sudan further support the presence of cattle in the region during the early ninth millennium cal BP (Honegger 2005:247–248). The earliest evidence of small domestic cattle from the central Sahara dates, however, to the eighth millennium BP (at Ti-n-Torha and Uan Muhaggiag; Gautier 1987b; fig. 1).

To date, the strongest evidence for domestication of cattle in Africa comes from a series of major studies of the genetic characteristics and biodiversity of contemporary cattle breeds. Changing genetic approaches are reviewed by Larson (2011). Initial analyses of maternal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) showed that African cattle shared a distinctively higher frequency of the T1 mitochondrial haplogroup than is common in other regions and a large proportion of unique haplotypes (Bradley et al. 1996). These findings are consistent with an independent African domestication, although the possibility of a demographic expansion of Near Eastern cattle in Africa could not be ruled out (Bradley and Magee 2006; but see Achilli et al. 2008). Recent analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms from whole-genome sequences derived from small numbers of cattle demonstrate that African breeds diverged early from the European taurine cattle (Decker et al. 2009). New analyses of high-resolution interspersed multilocus microsatellites on the male-specific region of the Y chromosome demonstrate the existence of an African subfamily in taurine cattle of the Y2 haplogroup (Pérez-Pardal et al. 2009). Associated analyses also indicate that neither the genetic diversity in the African mtDNA T1 haplogroup nor the diversity in the Y2 haplogroup is consistent with the bottleneck that would have been required to fix these haplotypes from Near Eastern taurine cattle (Pérez-Pardal et al. 2010; see also Bovine HapMap Consortium 2009). Taken together with data on variation in autosomal microsatellites (rapidly evolving regions of the nuclear genome) and other data on Y-chromosome variability in African cattle breeds (Bradley and Magee 2006; Hanotte et al. 2002), the genetic data as a whole point strongly to an independent African domestication of cattle (Pérez-Pardal et al. 2009, 2010).

Ethnographic studies suggest, however, that genetic and phenotypic change may have been slow in early northeastern-African cattle and that neither morphological nor genetic studies are likely to detect the early phases of this process. Given recurrent cycles of drought and disease, contemporary African pastoralists manage their herds for maximum growth by keeping a high proportion of females in herds (Dahl and Hjort 1976). However, the main intentional selective processes acting on African cattle are culling and castration, which affect males rather than females (Dahl and Hjort 1976; Ryan et al. 2000). Natural selection in the form of drought and disease often play a larger role in mortality than culling (Mutundu 2005), multiple bulls are common in herds, offtake is low (4%–8%), and culling often takes place after sexual maturity (Ryan et al. 2000). Such processes, together with some introgression with wild bulls, are likely to have worked against rapid morphological change in early pastoral herds and to have resulted in a postmanagement lag in morphological change.

Domestication of the donkey.

It has long been suggested that ancient Egyptians domesticated the donkey (Equus asinus), although the Near East has also been considered a possible area of origin. Egyptian Predynastic sites have yielded the earliest potential domestic donkeys, which date to the mid-seventh millennium cal BP (historic date 4600–4400 BC; Boessneck and von den Driesch 1990; table 1). Some faunal elements from these sites, zooarchaeologists argue, exhibit size decrease relative to the wild ass (Boessneck and von den Driesch 1990), but widespread morphological change was slow to develop in ancient Egypt. Evidence of bone pathologies from early dynastic donkey burials at Abydos (fig. 1) demonstrates that by approximately 5000 cal BP (historic date 3000 BC), First Dynasty Egyptian kings were using donkeys to carry heavy loads (Rossel et al. 2008). Rossel et al. (2008) show, however, that these animals were not yet morphologically distinguishable from the African wild ass.

Recent studies of genetic variability in modern donkeys suggest that prehistoric pastoralists may have domesticated donkeys on the fringes of the Sahara. Beja-Pereira and colleagues (2004; also Vilá, Leonard, and Beja-Pereira 2006) document the existence of two different haplogroups or clades of domestic donkeys. Their genetic-diversity data suggest two domestication events, both in northeastern Africa. Kimura et al.’s (2010) recent analysis of ancient DNA from the Nubian donkey (Equus africanus africanus) and the Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis) demonstrates that the Nubian wild ass was the ancestor of modern donkey Clade I but that the ancestor of donkeys of Clade II is currently unknown. This research also documents the ancient distribution of the Nubian wild ass and Clade I donkeys from the Atbara River and Red Sea Hills in Sudan and northern Eritrea across the Sahara to Libya, a geographic distribution that suggests that prehistoric pastoralists domesticated Clade I donkeys (Kimura et al. 2010). However, domestication by pastoralists or farmers of the northern Nile Valley during late prehistoric/early Predynastic times is also a possibility.

The Herding-Hunting Mosaic and the Spread of Pastoralism

In the central Sahara, cattle became common in the eighth to sixth millennium cal BP at sites such as Ti-n-Torha, Uan Muhaggiag, Uan Telocat, Adrar Bous, Gobero, Enneri Bardagué, and Wadi Howar (Clark et al. 2008; di Lernia 2006; Garcea 2004; Gautier 1987b; Jesse et al. 2007; Roset 1987; Sereno et al. 2008; fig. 1). The main advantages for hunter-gatherers of herding cattle over intensification of plant resources or reliance on hunting and gathering are thought to have been decreased reliance on local rainfall and increased predictability in daily access to cattle herds for blood, meat, and ceremonial purposes (Jesse et al. 2007; Marshall and Hildebrand 2002). Foraging continued, but the intensity of the new human-animal relationship would have required ownership patterns and schedules oriented to animal care and transformation of hunter-gatherer societies. Dependence on wild calories could have been somewhat reduced, however, by milking, a practice that archaeologists have tended to assume was adopted after herding for blood and meat and with some difficulty (but see Linseele 2010).

Different genetic bases for lactase persistence in Europe and Africa show coevolution between people and cattle and the strong selective advantage conferred by drinking milk (Tishkoff et al. 2006). Interestingly, recent research has documented lactase persistence among some contemporary African hunter-gatherers. Tishkoff et al. (2006, supplementary information) note that lactase persistence could be selected for by delaying weaning of infants and, moreover, that the trait is also adaptive for digestion of certain roots and barks. This suggests several pathways to lactase persistence among hunter-gatherers and raises the question of whether African herders milked their cattle earlier and incorporated dairy products into their diets with fewer digestive difficulties than previously thought. However, milking scenes depicted in prehistoric African rock art and in Saharan ceramics have so far not produced dates or residues that bear on the antiquity of milking in Africa (Jesse et al. 2007; Marshall 2000).

Oscillating periods of aridity and humidity resulted in periods of increased mobility and occasional depopulation of the Sahara (di Lernia 2002; Garcea 2004; Kröpelin et al. 2008). In the eighth to seventh millennia cal BP, herders combined livestock keeping with hunting and collection of wild grain in regions such as the Acacus Mountains (Gautier 1987b). At Adrar Bous and other sites near lowland lakes, herders also fished and collected shellfish (Gifford-Gonzalez 2005; Smith 1992; fig. 1). Cattle-focused rock art attests to the symbolic importance of cattle for Saharan herders (Holl 2004; Smith 1992, 2005). Hunter-gatherers also flourished during this period at sites such as Dakleh Oasis (McDonald 2008) and Amekni (Camps 1969; fig. 1), creating a mosaic of hunters and herders across northeastern Africa (fig. 1).

Through the mid-Holocene, grasslands became more arid, precipitation became increasingly unpredictable, and desert regions of the Sahara expanded. Northeastern Africans responded to these pressures by heightening mobility, relying on introduced sheep and goats, and decreasing use of wild cereals (Barich 2002; di Lernia 2002; Garcea 2004; Gautier 1987a). It was during this period that the donkey was domesticated (Rossel et al. 2008). Their use would have made increased residential mobility and dispersal of settlements from water possible and would have facilitated long-distance migrations (Marshall 2007).

Significant expansion of the geographic distribution of the dotted-wavy-line ceramic motif and distinctive human mortuary practices in the early seventh millennium cal BP reflect the southward movement of pastoralists, long-distance contacts among Saharan groups, and elaboration of pastoralist ideologies (Jesse et al. 2007; Keding, Lenssen-Erz, and Pastoors 2007; Smith 1992; Wendorf and Królik 2001). Just as in the Mediterranean and western Europe, however, the trajectories of small immigrant groups may have varied greatly (Özdoğan 2011; Rowley-Conwy 2011). Domestic stock appear to the south in the Sudanese Sahel by the early seventh millennium cal BP at Esh Shaheinab and Kadero (Gautier 1984a, 1984b) and by the mid-fifth millennium cal BP in Kenya (Marshall and Hildebrand 2002). Similarly, Saharan lithics and other traces of Saharan herders are first found in the West African Sahel by approximately 4500 cal BP (Jousse et al. 2008; Linseele 2010; Smith 1992). Di Lernia (2006) argues that the widespread ritual burial of cattle across the Sahara at the end of the seventh millennium BP represents a social response to rapid aridification. Cattle burials and associated ritual activity are a prominent feature of site E-96-1 at Nabta (Wendorf and Królik 2001). At Djabarona 84/13, in the middle of Wadi Howar from the beginning of the sixth millennium cal BP, more than a thousand pits are filled with cattle bones and relatively complete ceramic pots (Jesse et al. 2007; fig. 1). As far south as Kenya by the middle of the fifth millennium cal BP, large stone circles such as those at Jarigole were constructed as centers for human burial rituals by southward-migrating herders (Marshall, Grillo, and Arco 2011; Nelson 1995). Hunter-gatherers, however, continued to flourish after the movement of herders into these regions (Lane et al. 2007; Lesur, Vigne, and Gutherz 2007).

Domestication of African Plants

The earliest evidence for domestication of indigenous African plants with morphological change dates only to the beginnings of the fourth millennium cal BP (table 1). Although many Holocene hunter-gatherers of northeastern Africa relied heavily on wild Saharan cereals, high mobility and repeated abandonment of the region seem to have impeded long-term directional selection and morphological and genetic change. Instead, selection processes culminated in morphological change once Saharan herders settled in the southern reaches of the Sahara and more humid Sahelian regions and established more permanent settlements in areas that were still within or close to the edge of the wild range of Saharan species.

Sahelian herders—who also hunted, gathered, and fished—integrated cultivation of domestic pearl millet Pennisetum glaucum into their subsistence economies in one or two domestication events documented at or after 3898–3640 cal BP at sites west of Lake Chad, including Karkarichinkat Nord (KN05), Dhar Tichitt, Birimi, and Gajiganna (D’Andrea, Klee, and Casey 2001; Fuller 2007; Kahlheber and Neumann 2007; Manning et al. 2011; fig. 1, table 1). Morphologically, this is evidenced by changes in seed shedding and shape, although increases in seed size were delayed (D’Andrea, Klee, and Casey 2001). Fuller (2007) argues that the appearance of domestic pearl millet in India in the mid-fourth millennium cal BP indicates a somewhat earlier African domestication and rapid dispersal. Recent research has also shown that the cow pea Vigna unguiculata was also an early-fourth-millennium morphological domesticate, dating to ca. 3898–3475 cal BP at the Kintampo B-sites in the grasslands of central Ghana (D’Andrea et al. 2007; table 2). By contrast, African rice Oryza glaberrima was domesticated in the inland Niger delta of the Niger bend region by the early second millennium cal BP. On the eastern side of the continent, domestic teff Eagrostis tef and finger millet Eleusine coracana were cultivated by Aksumite populations in the Ethiopian highlands by the beginnings of the second millennium cal BP (historic date AD 150–350; D’Andrea 2008). The oil-seed noog Guizotia abyssinica is also present in Late Aksumite contexts (D’Andrea 2008). D’Andrea (2008) points out, however, that morphological change is difficult to identify in the small-seeded cereal teff, which was selected for reliable production under arid conditions rather than for increased seed size. In humid forested southwestern Ethiopia, Hildebrand (2003a, 2003b, 2007) has documented varied selection processes leading to domestication of yams Dioscorea cayenensis and ensete Ensete ventricosum. In these and other areas of Africa, domestic plants are thought to have been advantageous to pastoral hunter-fishers for risk minimization and greater predictability (D’Andrea et al. 2007; Kahlheber and Neumann 2007; Marshall and Hildebrand 2002).

Although morphological change occurred in a range of domesticated African plant taxa, it has been suggested that a number of African savanna plants were cultivated or intensively managed over the long term in ways that did not lead to morphological domestication (reviews in Marshall and Hildebrand 2002; Neumann 2005). Haaland (1999) and Abdel-Magid (1989) argued, largely on the basis of the ∼30,000 grindstones that were unearthed at the site of Um Direiwa, for cultivation of sorghum Sorghum bicolor in Sudanese sites dating to the seventh millennium cal BP (table 1). Mechanisms that they suggested for late morphological change include continued outcrossing between cultivated and wild populations and harvesting through beating into baskets or uprooting. This has led to arguments that sorghum was not morphologically domesticated until it was removed from its wild African range (Haaland 1999; but see Fuller 2003). Although mechanisms exist that may have caused late morphological change in African cereals and harvesting of wild grains was at times intensive, there is no macrobotanical evidence or indication of landscape modification that supports claims for cultivation of African grains before the early fourth millennium cal BP.

In the wetter tropical regions, there is evidence of long-term use of a number of forest taxa without morphological change. Long-term use of oil palm Elaeis guineensis and incense trees Canarium schweinfurthii has been documented across the humid tropics of Africa (D’Andrea, Logan, and Watson 2006; Mercader et al. 2006). This pattern is not confined to forests, however. D’Andrea, Logan, and Watson (2006:216–217) argue that Kintampo people living in the grasslands of central Ghana employed a system of arboriculture that did not rely on management strategies that would result in morphological change. Kahlheber and Neumann (2007) also note that a number of west African park savanna species, such as baobab Adsonia digitata and the shea-butter tree Vitellaria paradoxa, were protected and encouraged but never domesticated. Other wild plants that are still protected and sometimes actively sown in many different African environments include weedy green species ranging in status from crops to semidomesticated or wild (Kahlheber and Neumann 2007; Marshall 2001). Kahlheber and Neumann (2007:333) point out that in the West Africa Sahel, reliance on morphologically wild park savanna species became more evident when economies diversified and populations concentrated close to water 2,000 years ago. In many regions of Africa, Iron Age agriculturalists relied on a particularly broad range of resources, and farmers incorporated diverse domestic crops and managed plants, cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and donkeys into their agricultural systems and fished and hunted a wide range of wild-animal foods (Casey 2005; Neumann 2005; Plug and Voigt 1985; van Neer 2000).

This brings to the fore the question raised at the outset of whether such diverse subsistence strategies fit current conceptions of agricultural systems. Kahlheber and Neumann (2007:339) are doubtful whether “farming” is an appropriate term for some of these ways of life. Smith’s (2001, 2011) term “low-level food production” has been used in the region, but it does not fully capture the complexities of African settings. The question of whether the Kintampo should be considered “foragers,” “farmers,” or something else has also been reviewed by Casey (2005) and by D’Andrea and colleagues (D’Andrea, Logan, and Watson 2006:216–218; D’Andrea et al. 2007), who argue that although there are clear-cut cases of foragers or farmers in Africa, there are many others that defy simple categorization. Hildebrand’s (2003a) ethnographic research among the Sheko of southwestern Ethiopia and the literature on use of weedy greens in Africa (Etkin 1994; Fleuret 1979; Marshall 2001 and references therein) provide ample evidence that such subsistence strategies have long-term trajectories in many parts of Africa and cannot be dismissed as transitory.

Ethnoarchaeological Insight into Management, Selection Processes, and Domestication of the DonkeyJump To Section...

One approach to better addressing conceptual problems presented by questions of late morphological change and the diversity of economic systems in Africa is to consider pathways to domestication for particular species in light of the potential for morphological change, or lack thereof, in specific social and environmental contexts. The question that we address here is how the behavior of the African wild ass and management of donkeys by herders and small-scale farmers in Africa contribute to selection processes and the likelihood of development of archaeological signatures of domestication in the donkey. This analysis focuses on aspects of the biology and behavior of the donkey and its use as a transport animal that influence management practices in extensive pastoral and agricultural systems and are relevant (sensu Wylie 2002) to ancient settings for domestication. It is often argued, for instance, that sociability and the presence of a dominance hierarchy are desirable characteristics for potential domesticatability (Clutton-Brock 1992; Diamond 1997). African wild ass do not, however, fit this profile. The extant Somali wild ass, or dibokali, is solitary or forms groups with weak short-term associations. It also lacks a pronounced dominance hierarchy (Klingel 1974; Moehlman 2002). This social system profoundly influences donkey behavior under human management.

Recent ethnoarchaeologial research on donkey use and management among Maasai households in Kajiado District of southern Kenya provides the first detailed information on selection processes in a pastoral social and economic context. During 2006, Lior Weissbrod lived in Maasai communities in the study area and collected interview and participant observation data from 26 women from eight households spread among six different pastoral settlements (table 3). The study focused on use and daily management, herd composition, mortality, and breeding behavior. After a 2-year period of severe drought (2004–2006), the donkey holdings of households participating in the study were reduced but still totaled 65.

http://www.jstor.org/literatum/publisher/jstor/journals/content/curranth/2011/658481/658389/20111013/images/large/tb3.jpeg

Donkeys were not regarded as food. They were considered women’s animals, important for transport but without the symbolic status of cattle. Women were the caretakers of donkeys and used them to carry household goods during residential moves, to collect water, and to take intermittent trips to trading centers. Donkeys also carried meat, firewood, and water for large ceremonies. During the dry season, women went long distances for water every other day, returning with a typical load of 50 L per donkey. Children herded household donkeys with the calves, but during the wet season, donkeys were free ranging. Many families penned donkeys within the settlement thorn fence or in calf enclosures at night for protection against predators.

Our data show that the use of donkeys in Kajiado enhanced the flexibility and stability of local herding systems (see also Marshall 2007; Marshall and Weissbrod 2009). Families in the study area who did not own donkeys could not move as a whole away from permanent sources of water and were unable to make optimum use of available grazing. Donkeys were, nevertheless, managed less than other livestock. Marshall (2007) previously noted that the ability of donkeys to dig for water and to protect themselves from predators more successfully than other livestock was associated with low levels of management, which might result in low levels of selection. Our data show that behavior was a factor but that the level of use of donkeys in the study area ultimately determined the degree to which donkeys were herded and penned.

In addition to management practices, we also collected information on reproduction and desired characteristics of donkeys that might be selected for through strategic breeding. Women that we talked to particularly valued strength and calmness in a donkey. Some also mentioned the importance of disease and drought resistance, although they noted that donkeys were less vulnerable to these hazards than other livestock. We found, however, that participants in the study made no attempt at all to influence mate choice among donkeys or to breed for particular characteristics. The ancestry of a particular donkey was unknown except for the female parent. By contrast, research on cattle genealogies shows that Maasai herders memorize these in great detail for several generations (Ryan et al. 2000). The lack of strategic breeding of donkeys is influenced by donkey behavior and herd compositions but is also related, at least in part, to the fact that Maasai herders do not use donkeys as symbols of social transactions in the same way that they do cattle or value color distinctions ideologically.